August 20, 2002. Exactly ten years ago tonight, a friend and I went to a theater on Long Beach Island to see one of my favorite musicals, Lerner and Loewe's Camelot. I had read the play in tenth grade English class, and it became an instant favorite. The music was dynamite, and something about the character of Arthur just clicked for me.

However, after reading the play and picturing it, I was severely disappointed by the actual performance at the theater. The curtain rose on a flamboyant knight (in retrospect, I suppose flamboyance could work for a colorful place like T. H. White's Camelot, but it just struck me as being way out of character for the piece). The Merlin was stiff, melodramatic, and sing-songy. I suppose the Guenevere was okay. But the Arthur, my God. From first moment to last, the actor came across as snobby and cynical, which is all wrong for a character who, like Cinderella, was orphaned, raised as a servant to a noble, wealthy family, then pulls a sword from a stone and suddenly becomes "King born of all England." Arthur, in this play, is not cynical; he is boyish to the very end, even when he has lost everything he built and everyone he loved. He is—most of all—idealistic. He wants to create a society where there will be no war or suffering, where people will be governed by law and fairness, and where might does not make right, but where, instead, might is used FOR right. If ever ideals made for a better future, these are they. That is why T. H. White called his book The Once and Future King; these are the ideals for the future—they have to be fought for and worked for. These are the ideals that we as a culture—and I—want to live by.

But the performance of this play wasn't so hot. So when we got home, I turned to my friend and told him that in exactly ten years, I wanted to play King Arthur on stage and do it right. I even wrote down the date and put it in my hardcover Camelot libretto.

This was not the first time I wanted to one up a performer. When I was in middle school, my grandmother and her friends took me to hear Andrea Bocelli sing at the Meadowlands. I was very jealous of the attention these ladies had been paying to Mr. Bocelli of late, and as I wasn't as impressed by his voice as I was by Luciano Pavarotti's, I decided that I could beat Andrea Bocelli at his own musical game. That was when I decided to become an opera singer and travel the world.

That decision was fourteen years ago, and so much has passed since then. I started loading up on opera cd's. I must have learned the music of three or four operas by heart that year. I would close the door to my room and enact the closing scene of Rigoletto, until I gave up that opera for Lent. Little did I know, I couldn't actually sing a note just yet, so I started taking weekly singing lessons from a retired baritone from the Met. I always showed zeal for my interests.

But something about singing (and acting) never quite fit for me. Maybe it was that school work came more naturally for me than music. Maybe it was that I had an easier time learning Italian than I did reproducing and sustaining musical tones. I picked up much Italian vocabulary exclusively from the operas I had memorized and learned the grammar from a Barron's book. Additionally, I was making top grades in my French and Spanish classes at school. And I picked up a few words of Russian from opera and from my aristocratic Russian neighbor, who was like a great-grandmother to me. I loved opera, but I was being pulled (only partly consciously) in another direction.

In college, I continued to pursue language studies, both for class and on my own time. For class, I studied Italian literature, as well as Latin and Ancient Greek. On my own, I learned a few words of Biblical Hebrew as a freshman and then got into Wagnerian opera big time as a junior. Once again, I was learning large chunks of libretto by heart, and this time the German started to make sense using only translations—no dictionaries or grammar books. I also picked up some Icelandic from the Poetic Eddas and some Old English from the epic Beowulf.

Since then, I've been through so much change. My grandmother passed away seven years ago, and I know now how large a role she played in my life, having been a fixture from birth. I lost a cousin in a fatal car accident, and learned for the third time how short life can be. I lost my uncle in the World Trade Center eleven years ago and have seen my large, closely knit extended family torn apart by grief and strife, and known that both sides are in pain because of it. I was once a Catholic, but I stopped going to church a long time ago—when I stopped finding answers to my questions in Sunday sermons—when I started having questions that were not brought up in Sunday sermons. I've questioned God, justice, life, religion, psychology, subjectivity, reality, suffering. In short, the entire foundation on which my life had been built has broken down. My coming of age was distinctly marked by change, both real and symbolic. But I asked questions. And I have found people who could find complex answers to some of those questions. I did not do the traditional thing. I did not go directly from college to work or to grad school. I did go, however, to the works of artists, scholars, filmmakers, and philosophers who had passed that way and had asked the same questions before me. I have found answers, at least a few working answers. I once stood in a pile of rubble. But the cloud of dust has cleared. And like the skinny Englishman and the title character at the end of Zorba the Greek, I laugh!

In the end, the ten year goal I set for myself has not come true. I am not on Broadway or at Lincoln Center singing Camelot or Rigoletto. But I am really happy with the course of my life anyway. I did the Bohemian artsy thing, like any young artist should do. I set out with a career plan, with a variety of plans actually, but I changed when time changed. I haven't tried to force my way headfirst through a wall. I feel at peace. I'm following the Dao, and am in harmony my own nature, which makes me much happier than trying to become an opera singer or a literary scholar. I know more about myself and what to expect from myself than I did ten years ago. Looking back, I think I can see where my natural talent was all along. And I think I have a few ways to go about my goals in life using those talents in particular.

So like Arthur at the beginning of Lerner and Loewe's play, it can't be said that I've achieved my destiny; I've "stumbled upon it." And like Arthur at the end of the play, I haven't let disappointment and destruction break my spirit. I look forward to a future where, in spite of tremendous labor against the darkness, there is hope for the survival of a little bit of light. Impermanence does not deter me anymore. Positive action, whether it has meaning or not, and knowing it, is the solution. It's this that makes life worth living. It's this that gives meaning to the suffering which is everywhere. After many years, Camelot, with its resilience, still means something to me. And that meaning matters more to me than any dream I made for myself years ago.

I've been down strange paths, on my own adventures of exploration. What better place to share my adventures and my thoughts about our world than a blog!

Monday, August 20, 2012

Friday, August 17, 2012

Culture vs. Civilization

Recently, I read a book by Stephen Prothero called God Is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions That Rule the World and Why Their Differences Matter. I was also speaking with my cousin-in-law Paul, who is English and now an American citizen and resident as well. Paul and Mr. Prothero both made the same observation, one that I found intriguing: that the United States tends to be more religious than Europe. I think this observation is accurate and wondered why that might be, especially at a time when religion is of primary importance to many people in most other part of the world. Europe was also very religious (sometimes violently so) right into the 1600's and 1700's. Where then does this modern European apathy come from? That is going to be the subject of this particular blog post.

Interestingly enough, a sharp decline in Europe's religiosity can be noted around the time of the Age of Reason. This was the era that produced Thomas Jefferson, Isaac Newton, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. This period represented an emphasis on logic in philosophy, objectivity and fair representation in governance, the dominance of form and aesthetic beauty in the arts and architecture, and scientific investigation into the phenomena of the natural world.

However, around the year 1800, significant changes explode into the world. Emotion irrupts into politics and the arts. We see a bloody overturn of the government in the French Revolution, liberal ideals blended with imperial megalomania in the person of Napoleon, whose conquests spread those ideals and inspired democratic revolutions throughout Europe during the following decades, as well as a stormy irruption of emotion into the arts, which produces Beethoven and Wagner in music as well as Lord Byron and later the Gothic style of literature in Germany and Britain. The 1800's saw the monumental unifications of Germany and Italy, as well as struggles for independence, all of them achieved successfully by the year 1919, throughout all of Europe, including Greece, Hungary, Poland, Norway, and among all the peoples of the Balkans. In addition to the revolution in politics and art, new ideas on gender roles and family were sparked, and a French woman wrote books under the masculine pen name of George Sand, wore men's clothes, smoked men's cigars, and lived out of wedlock with her more docile male lover, Frederic Chopin. The 1800's also saw the recognition of the equality of mankind, the abolition of slavery in the United States and of serfdom in Imperial Russia. The century saw the spread not only of democracy but also the birth of a radical new idea of communal property ownership, known as communism. Scholars such as Max Müller began the laborious study of Ancient India and the Far East, and philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche introduced Europe to revolutionary Oriental ideas of subjectivity and perspectivism; pioneers such as Sigmund Freud began to explore the depths of the human psyche, while scientists probe the existence and composition of the elements, of genetics, and of the origin of species. During the whole period, we see new and radical ideas in the arts, sciences, politics, and philosophy, and decreasing interest in the Church, even a propensity among some intellectuals to reread Christianity as an early socialist movement (see for example the final pages of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle).

What we see, then, as early as two centuries ago is a breakdown in the traditional values and norms of Europe. This paves the way for the Koyaanisqatsi, the Götterdämmerung, of today—for a civilization out of touch with itself, out of sorts, and spinning ever more wildly like a top losing momentum, ready to fall over and stop turning altogether.

Last week I began reading Sigmund Freud's book Civilization and Its Discontents. An interesting idea, which this book presents, is the idea that culture is a spontaneous byproduct of human creativity. When we write a play that plumbs the depths of the human character, such as Hamlet or Oedipus, that is culture. When we build a cathedral with towering pillars, elaborately carved gateways, gilded ceilings, and beautiful stained glass windows, that is culture. When humans act and create, the result is culture. Art and culture, then, are a reflection of ourselves, the creators. If we look at the art of different periods of a culture, we can learn something about the psyche and values of the people who produced that culture. I would like to explore this idea a little further and examine visually some of the cultural landmarks and developments of our European heritage over the last five to seven centuries. (For those of you who are curious: no, beyond a few short paragraphs, I have not yet read Oswald Spengler's Decline of the West.)

Lorenzo Ghiberti's Story of Joseph, Doors of the Baptistry, Florence (1425)

Interior of the Church of the Gesù, Rome

Borghese Chapel, Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome

Salvador Dalí's Perseus

In the modern period, images of subjects are disordered—look at the odd proportions and positions of body parts in Picasso's work. We see abstraction and surrealism. The general picture is of chaos, madness, or even sickness. (I'm reminded of Fellini's film 8 1/2, where the main character, trapped in his car in a tunnel in a traffic jam, is seized by claustrophobia, rolls down the car window, and climbs out.) The art, and the greater seeking for psychological help, seems to reflect the sorrows of the changes and conflicts of the Twentieth Century: the Russian Revolution, two World Wars, the Holocaust, the atomic bombs. The glorification and idealization of man in the Renaissance and the search for knowledge of the Age of Reason have put the tools of destruction into the hands of the man of Europe, and with them, he has nearly blown himself up. He has not yet, however, reached his end, and that gives cause for hope. If Europe is less religious than America, Europe, having been more directly torn apart by this turmoil, is in a much more skeptical and reflective position than America. Europe is still very much recovering from the two World Wars—spiritually and psychologically. We could view this period as a culture-wide or continent-wide examination of conscience. When Europe emerges, there will be something very different in its values and in its ideals and practices.

I believe it will take a very large, culture-wide effort of planning and soul-searching to set the top aright and set it moving stably once again. It will require a complete revaluation of our history, of our languages, of our culture, and of our beliefs—in other words the tremendous pangs of labor—before we can give birth to a new culture with new values (and probably a new religion). As it stands, our traditional values are not in place—new developments in science and in politics have put us radically out of touch with the Christianity of the Middle Ages. One has only to compare the art of Giotto with the art of Picasso to see this. And a return to such values is simply not possible, given the journey that we have made and the knowledge that we have incorporated along the way.

Interestingly enough, a sharp decline in Europe's religiosity can be noted around the time of the Age of Reason. This was the era that produced Thomas Jefferson, Isaac Newton, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. This period represented an emphasis on logic in philosophy, objectivity and fair representation in governance, the dominance of form and aesthetic beauty in the arts and architecture, and scientific investigation into the phenomena of the natural world.

What we see, then, as early as two centuries ago is a breakdown in the traditional values and norms of Europe. This paves the way for the Koyaanisqatsi, the Götterdämmerung, of today—for a civilization out of touch with itself, out of sorts, and spinning ever more wildly like a top losing momentum, ready to fall over and stop turning altogether.

Last week I began reading Sigmund Freud's book Civilization and Its Discontents. An interesting idea, which this book presents, is the idea that culture is a spontaneous byproduct of human creativity. When we write a play that plumbs the depths of the human character, such as Hamlet or Oedipus, that is culture. When we build a cathedral with towering pillars, elaborately carved gateways, gilded ceilings, and beautiful stained glass windows, that is culture. When humans act and create, the result is culture. Art and culture, then, are a reflection of ourselves, the creators. If we look at the art of different periods of a culture, we can learn something about the psyche and values of the people who produced that culture. I would like to explore this idea a little further and examine visually some of the cultural landmarks and developments of our European heritage over the last five to seven centuries. (For those of you who are curious: no, beyond a few short paragraphs, I have not yet read Oswald Spengler's Decline of the West.)

The Early and High Renaissance (1300's-1500's)

Form- The word "form" derives from the Latin word forma, which has two meanings: 1) form and 2) beauty. As an example of this, the Latin word formosa survives today as the Spanish word hermosa, and both words have the same meaning: "beautiful." To the Romans, then, form and beauty were synonymous, and it is this connection between the two of them that drives the rebirth of Classical (Greek and Roman) aesthetic values that is known as the Renaissance. During the high period of the Renaissance, form and idealism were the mandates of art and architecture. Aesthetic beauty and visually pleasing figures were sought and, in fact, created in the arts. In the works of Michelangelo and Raphael, we see the epitome of what man can be: a noble creature full of knowledge and wisdom, aspiring towards greater deeds than have ever been accomplished before. Characteristics of this period are aspiration, political ambition, and a spirit of exploration (two continents previously unknown to Europeans are discovered). The body is beautiful and muscular. Proportion and symmetry reign, be it in architecture or the human body. Objects and persons depicted or sculpted resemble the actual objects and persons: there is idealization, but no abstraction. There is reverence for the sacred. Every inch of a painting, of a sculpture, of a cathedral reveals an artist or a priest or a politician glorying in the talent of man. Diagnosis: in the Europe of this time, man is strong, virile, robust, and healthy.Early Renaissance:

Cathedral of Santa Maria di Fiore (Duomo), Florence

Giotto's Mourning of Christ, Scrovegni Chapel (c. 1305)

Giotto's Mourning of Christ, Scrovegni Chapel (c. 1305)

High Renaissance:

Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa (c. 1503–1519) and Vitruvian Man (c. 1497)

Lorenzo Ghiberti's Story of Joseph, Doors of the Baptistry, Florence (1425)

Raphael's School of Athens, from Raphael's Stanze, Vatican Museums (c. 1510)

Click here for a larger image.

Click here for a larger image.

Michelangelo's Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel (c. 1511)

Michelangelo's Last Judgement, Sistine Chapel (1537-1541)

Click here for a larger image.

Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1545)

The Baroque Period (1600's)

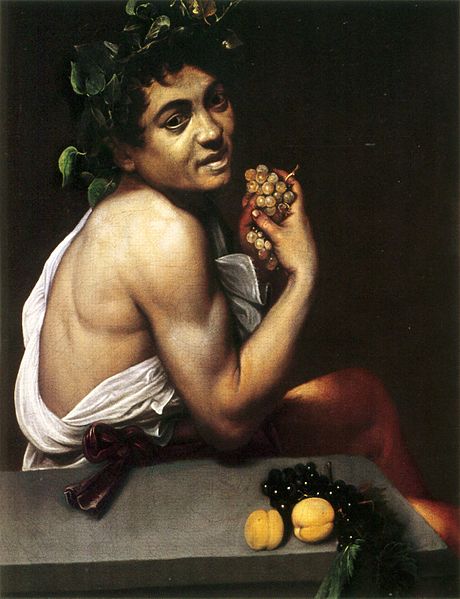

This period is followed by the Baroque period of the 1600's-early 1700's. The Baroque period is typified by extra ornamentation. In architecture, double columns often appear for aesthetic decoration, where only one load-bearer would have sufficed. Enjoyment and mild excess are key to this period; in painting we often see rich gardens and platters of fruits. In painting, chiaroscuro arises: subjects sit in dark backgrounds, lit by a single source of light, which flows over the subjects' contours and casts shadows to the corners. Though highlighting the shadows and lending seriousness to its subjects, the chiaroscuro technique shows a revelry in contemplation.Baroque:

Church of SS. Annunziata, Sulmona

Interior of the Church of the Gesù, Rome

Borghese Chapel, Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome

Chiaroscuro:

Georges de la Tour's Penitent Magdalene (c. 1638-1645)

Caravaggio's St. Francis in Ecstasy (c. 1595)

The Neoclassical Period (late 1700's-early 1800's)

Following the Baroque comes the Neoclassical Period in art. In philosophy, this is also known as the Age of Reason or Age of Illumination, while in music, it is known simply as the Classical period. The word "Classical" means "like the Ancient Greeks and Romans," and the Neoclassical is the second rebirth of Greco-Roman ideals. During this movement, there is a return to the idealization of the human and of the body that was seen in the Renaissance. Majesty, reason, and zeal are characteristic. Greco-Roman myths are often major subjects. Throughout this style, subjects are still clearly recognizable. Lines are clear, edges of subjects and objects are distinct. Beauty is striven for. The tone is heroic.Neo-Classicism:

Jacques Louis David's Death of Socrates

Jacques Louis David's Oath of the Horatii

Jacques Louis David's Napoleon Crossing the Alps

Antonio Canova's Paolina Borghese (Napoleon's sister) as Venus Victrix

Gianlorenzo Bernini's Apollo and Daphne

The Romantic Era and Impressionism (1800's)

On the other hand, when we look at the art of the Romantic era (early to mid-1800's), we see the beginning of a breakdown in forms. Emphasis is now no longer on form and beauty but on feeling and the sublime. Mood is prevalent. Storm and stress (Sturm und Drang) rage in music. Haunting, gothic images abound, in painting as well as literature (Poe, Brontë, and Mary Shelley flourish in this period). We see more shadows, perhaps even mist. Later, with Impressionism, images and sounds become soft and a little blurry. In painting, we see pointillism, points of dots close enough together to seem to be an image, when viewed from a distance. Emphasis is no longer on distinct edges but on more vague impressions of images. With the Romantic period, form has broken down, and with Impressionism, the fragments of form are beginning to melt as if into jelly.Romanticism:

Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer Above the Mists

John Henry Fuseli's The Nightmare

Pointillism and Impressionism:

Georges Seurat's Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884)

Van Gogh's Self-Portrait (1887) Auguste Rodin's Adam (1880)

Claude Monet's Water Lilies (1907)

Claude Monet's Water Lily Pond and Weeping Willow (1916-1919)

The Modern Period (1900's)

What we see in the Twentieth Century, then, is the complete breakdown of form in art. We may still like the artwork or dislike it, love it or hate it. But in visible contrast to the earlier Renaissance and Classical periods, emphasis is no longer on idealization, aesthetic beauty, or form. We see images which would traditionally be viewed as chaotic, abstract to the point of being completely unrecognizable, and sometimes what many would call, in grossly subjective terms, ugly. We can also hear this in the dissonance of the music, Igor Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, for example. It is significant that art begins to look ugly right around the time that psychology and psychoanalysis emerge. Art, as a product of our psyche, is a reflection of us as a culture. We begin to see grossness and chaos in the arts as we begin to see these things in ourselves and go to doctors to seek mental treatment.Expressionism:

Edvard Munch's The Scream

Futurism:

Umberto Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913)

Cubism:

Pablo Picasso's Untitled (1923) Pablo Picasso's Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1910)

Surrealism:

Salvador Dalí's Persistence of Memory (1931)

Salvador Dalí's Perseus

Abstract Expressionism:

Jackson Pollock's Number 8, 1949

Architecture:

Guggenheim Museum, New York

The Absurd:

In modern times, nothing is sacred. Sometimes in these advanced stages of decay, we get really silly.

Marcel Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q.

(The French pronunciation of these letters gives us

the French words: Elle a chaud au cul,

which means, "She has a hot ass.")

The Pillsbury Dough Boy as The Scream

(currently circulating on Facebook)

In the modern period, images of subjects are disordered—look at the odd proportions and positions of body parts in Picasso's work. We see abstraction and surrealism. The general picture is of chaos, madness, or even sickness. (I'm reminded of Fellini's film 8 1/2, where the main character, trapped in his car in a tunnel in a traffic jam, is seized by claustrophobia, rolls down the car window, and climbs out.) The art, and the greater seeking for psychological help, seems to reflect the sorrows of the changes and conflicts of the Twentieth Century: the Russian Revolution, two World Wars, the Holocaust, the atomic bombs. The glorification and idealization of man in the Renaissance and the search for knowledge of the Age of Reason have put the tools of destruction into the hands of the man of Europe, and with them, he has nearly blown himself up. He has not yet, however, reached his end, and that gives cause for hope. If Europe is less religious than America, Europe, having been more directly torn apart by this turmoil, is in a much more skeptical and reflective position than America. Europe is still very much recovering from the two World Wars—spiritually and psychologically. We could view this period as a culture-wide or continent-wide examination of conscience. When Europe emerges, there will be something very different in its values and in its ideals and practices.

I believe it will take a very large, culture-wide effort of planning and soul-searching to set the top aright and set it moving stably once again. It will require a complete revaluation of our history, of our languages, of our culture, and of our beliefs—in other words the tremendous pangs of labor—before we can give birth to a new culture with new values (and probably a new religion). As it stands, our traditional values are not in place—new developments in science and in politics have put us radically out of touch with the Christianity of the Middle Ages. One has only to compare the art of Giotto with the art of Picasso to see this. And a return to such values is simply not possible, given the journey that we have made and the knowledge that we have incorporated along the way.

Thursday, August 2, 2012

Chick-fil-a, Part 2

| And people wonder why I am the way that I am. |

"Everybody's very upset about it but I say, let her slide on this. I mean, let the woman slide. I know what you're saying, "Bill, you're Irish." I'm a hundred per cent Irish. I'm an American - but the blood is green. ... I say, let her slide. I mean, she was just 'faced, that's all. She was just 'faced. I mean, she hits Chicago, she goes out to dinner with some wild green animals in that town, has a few cocktails and she just gets 'faced, you know. She turns to the Irish mayor of Chicago, Jane Byrne, says the Irish are pigs. Tell me she wasn't too 'faced or nothin'. Not much she wasn't. So let her slide. You know, when somebody gets 'faced, you let 'em slide on that, especially, you know, a girl -- when they get 'faced. And, especially, a member of the royal family, you know?

"Back in England, she's the queen's sister. She can't get weird at all, you know. And, you know, if people don't let you get weird nowadays, you get irreversibly weird, I think. So let her slide! Come on, this is America. Look -- Princess Margaret is a pig. She's a slut, she's a tramp, she's a slime bucket. So what? Right. Exactly. I can say this. She's lettin' me slide. ... You know why? Because this is America. And because I am 'faced. ... I am completely 'faced. I don't know if this is even makin' any sense. Listen, she was 'faced. I am 'faced. So let us both slide on this. God, am I 'faced. ... Jane, are you as 'faced as I am? ... I am completely 'faced."

Sorry I couldn't find the video clip. You can read the full sketch here, including some Roseanne Roseannadanna at the end.

So, in other words, we should let people slide for what they say when they're drunk, right? Riiight. So I'm gonna let Dan Cathy slide for what he said because he was drunk, right? Riiight. Wait, what's that you say? He wasn't drunk? Okay then, in that case, I say screw the man and his fried chicken. I can eat better chicken than that at my mom's kitchen table. And I just did! So I close my words on Dan Cathy with Eddie Murphy's impression of Richard Pryor: "Tell him I said to have a Coke and a smile and shut the ---- up!"

| Bill Murray wants YOU to be a Ghostbuster, not a bigot. |

Did you catch what that duck says at the end of the cartoon, when he hugs the Statue of Liberty? "I'm glad to be a citizen of the United States of America."

And many people nowadays are attempting to mask their bigotry and hatred with the name of God, the Bible, and tradition. But it is really a mask for ignorance. I am not talking about my friends and other caring religious people. I know that there are so many religious people out there who are struggling with traditional teachings and interpretations but who still want to accept and support their friends and their needs. I know it's not easy to bend the rules, or to learn to look at things from a new perspective, or to be in conflict with what you were taught. I know that from experience. For me, it took a real breakdown and examination of everything I had grown up with. But I have found that it is possible to embrace both the past and the future. It is possible to live within a traditional framework as well as complete your own personal mission in life. And I can testify from personal experience that we are living in a time when, more than ever, it is imperative to breakdown and examine the ideas and traditions we were raised with. It is possible to be faithful to the past and to move forward.

I come from a Catholic background, and I am a first generation American on my mother's side. I grew up with a very close attachment to my Old World grandparents, so close that I have normally always identified more with them and with their traditions than with other Americans. I have studied the Renaissance and the Romantic era as well as the Ancient Greek and Roman eras. I have even lived in Italy for three months. And because our culture is so young, people in this country have almost no idea how old the world really is and how much of the ancient world survives today. It survives in old countries such as Italy, India, and Egypt. The Middle Ages and Enlightenment are also alive today.

All society and civilization is built upon layers, like Constantinople, as is the structure of our psyche. But you also have to define yourself in relation to that psyche, to that civilization, to that system of traditions. You cannot let tradition dictate who you are. Not in the West. You are not living in India and being told to accept and fit the mold into which you were born. You were born in a land with a chance to to define yourself and build your life as you choose. You always carry your tradition and your past with you. But you are another step forward. If you stop and do not take that step forward, your line, your whole family's history, and your own development, stop with you. But if you take that step, you are not leaving behind all tradition. All you have to do is turn around and see the line of the myriad footsteps of your ancestors still in the sand, leading up to where you are now.

| Flush that bigotry out with some Colon Blow. |

My Take on Chick-fil-a

Yes, in this country we have freedom of speech, and it is one of the

most important rights that we have. But with that right comes

responsibility. Just because you CAN say something doesn't mean that you

SHOULD. For the record, hate speech is technically protected by the

First Amendment; that doesn't mean that you should use it. Does anybody

remember Don Imus and his remarks about that black basketball player in

2007? But even though the First Amendment technically protects hate

speech, that is not what it was intended to do. The First Amendment was

designed to protect people from oppression by the secular and religious

authorities. Once upon a time, people like Galileo were placed under

house arrest for claiming that the earth goes around the sun. Once upon a

time, people like Martin Luther were excommunicated for standing up,

criticizing corruption, and voicing their convictions. Once upon a time,

people like Giordano Bruno and Savonarola were burned at the stake for

what they taught and for what they believed.

| The statue of Giordano Bruno in Rome's Campo de' Fiori |

| The Burning of Girolamo Savonarola in Florence, 1497 |

Ratified in 1791, less than a hundred years after the Salem Witch Trials, the First Amendment was designed to protect us, life and limb, from intellectual oppression and persecution. It is one of our most sacred laws in the land. It is designed to keep us free from the fear that people live with every day in North Korea and Iran, and from the fear that the name of Nazi Germany still inspires in us. The Chick-fil-a controversy is NOT an issue of freedom of speech. Dan Cathy is NOT being being put on trial or persecuted by the government for his remarks. Like it or not, there is no denying that his right to speak his mind is protected by our laws, nor is that right in any way in jeopardy by our government. And I believe in that right. But for his abuse of the responsibility that goes with that right, I say he's an ass. And I'm exercising my right to say that. Whether he's an ass of the gluteus maximus or of the barnyard variety, I leave to my readers to decide. I exercise my right bluntly, but with a modicum of class and verbal ambiguity. Words are dangerous, especially to the one who speaks them, and their use requires tact, which is an important lesson that I am always learning. If Don Cathy makes an ass of himself, that is not a crime. I don't think he should go to jail for it, nor is he likely to. But he still made an ass of himself. Would you want to do that?

I want to make an analogy here. In one of my college classes, I heard the opinion of someone from South Jersey who announced that he flies the Confederate flag. He claimed that he does so because to him the Confederate flag is not a symbol of hatred and slavery but a symbol of states' rights. Well, I can support someone's belief in the rights of states, but there was a flaw in this young man's logic: because his claim ignores the fact that the right that the Confederate states wanted was the right to own another human being. The claim by those who fly that flag today (some of them here in New Jersey) obscures the real issue of the 1860's, which was NOT the right of states to secede from the Union but the question of whether we are going to recognize another human being as a full and equal human being under the law. The country was NOT divided by the issue of states' rights but by the issue of slavery vs. abolition. And the issue at hand is NOT one of freedom of speech or freedom of religion but of whether or not we are going to butt into another person's life and call it law and righteousness. The issue is whether or not we are going to fully end decades of ignorance and centuries of shame and oppression and finally recognize another person as a full and equal human being, even if we do not understand one of their basic instincts. I never understood why people love football, but I don't think it's morally wrong. I don't understand what people like about hamburgers—I find them rather dry—but I don't think that the tastebuds and preferences of hamburger lovers are morally degenerate. But that is what has been imputed to gay men and women for centuries. THAT is what this issue boils down to, nothing more, nothing less.

In the past, the Bible has been used (on television) to justify slavery. I can remember a video clip from a class or a documentary, in which a Southern politician or reverend went on television during the Civil Rights movement and read the Biblical story of Noah's curse of his son Ham and used this passage to justify the slavery of black people by whites. Nor, apparently, was this man the first to do so; see the Curse of Ham. But we did not let that interpretation win out in the 1960's. We recognized it as bigoted, oppressive, and wrong. We followed Martin Luther King instead of the segregationists, whose names we do not even remember. For centuries, the Bible has also been used to justify homophobia. Are we going to let that interpretation win out? Are we going to use the Bible to justify the Inquisition once again? There are other alternatives. Hatred does not have to win out.

Even the Jim Henson Company is on board with the Chick-fil-a boycott. This tells us something: a company named after a man who spent his life educating and entertaining children does not want those children to learn to hate themselves or others and to stifle their own happiness, creativity, and growth. Dan Cathy is wrong. You do not have the right to tell someone else he or she cannot get married. No one has that right. In the words of Toula's mother in My Big Fat Greek Wedding, "No one has that right."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)