Recently, I read a book by Stephen Prothero called God Is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions That Rule the World and Why Their Differences Matter. I was also speaking with my cousin-in-law Paul, who is English and now an American citizen and resident as well. Paul and Mr. Prothero both made the same observation, one that I found intriguing: that the United States tends to be more religious than Europe. I think this observation is accurate and wondered why that might be, especially at a time when religion is of primary importance to many people in most other part of the world. Europe was also very religious (sometimes violently so) right into the 1600's and 1700's. Where then does this modern European apathy come from? That is going to be the subject of this particular blog post.

Interestingly enough, a sharp decline in Europe's religiosity can be noted around the time of the Age of Reason. This was the era that produced Thomas Jefferson, Isaac Newton, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. This period represented an emphasis on logic in philosophy, objectivity and fair representation in governance, the dominance of form and aesthetic beauty in the arts and architecture, and scientific investigation into the phenomena of the natural world.

However, around the year 1800, significant changes explode into the world. Emotion irrupts into politics and the arts. We see a bloody overturn of the government in the French Revolution, liberal ideals blended with imperial megalomania in the person of Napoleon, whose conquests spread those ideals and inspired democratic revolutions throughout Europe during the following decades, as well as a stormy irruption of emotion into the arts, which produces Beethoven and Wagner in music as well as Lord Byron and later the Gothic style of literature in Germany and Britain. The 1800's saw the monumental unifications of Germany and Italy, as well as struggles for independence, all of them achieved successfully by the year 1919, throughout all of Europe, including Greece, Hungary, Poland, Norway, and among all the peoples of the Balkans. In addition to the revolution in politics and art, new ideas on gender roles and family were sparked, and a French woman wrote books under the masculine pen name of George Sand, wore men's clothes, smoked men's cigars, and lived out of wedlock with her more docile male lover, Frederic Chopin. The 1800's also saw the recognition of the equality of mankind, the abolition of slavery in the United States and of serfdom in Imperial Russia. The century saw the spread not only of democracy but also the birth of a radical new idea of communal property ownership, known as communism. Scholars such as Max Müller began the laborious study of Ancient India and the Far East, and philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche introduced Europe to revolutionary Oriental ideas of subjectivity and perspectivism; pioneers such as Sigmund Freud began to explore the depths of the human psyche, while scientists probe the existence and composition of the elements, of genetics, and of the origin of species. During the whole period, we see new and radical ideas in the arts, sciences, politics, and philosophy, and decreasing interest in the Church, even a propensity among some intellectuals to reread Christianity as an early socialist movement (see for example the final pages of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle).

What we see, then, as early as two centuries ago is a breakdown in the traditional values and norms of Europe. This paves the way for the Koyaanisqatsi, the Götterdämmerung, of today—for a civilization out of touch with itself, out of sorts, and spinning ever more wildly like a top losing momentum, ready to fall over and stop turning altogether.

Last week I began reading Sigmund Freud's book Civilization and Its Discontents. An interesting idea, which this book presents, is the idea that culture is a spontaneous byproduct of human creativity. When we write a play that plumbs the depths of the human character, such as Hamlet or Oedipus, that is culture. When we build a cathedral with towering pillars, elaborately carved gateways, gilded ceilings, and beautiful stained glass windows, that is culture. When humans act and create, the result is culture. Art and culture, then, are a reflection of ourselves, the creators. If we look at the art of different periods of a culture, we can learn something about the psyche and values of the people who produced that culture. I would like to explore this idea a little further and examine visually some of the cultural landmarks and developments of our European heritage over the last five to seven centuries. (For those of you who are curious: no, beyond a few short paragraphs, I have not yet read Oswald Spengler's Decline of the West.)

Lorenzo Ghiberti's Story of Joseph, Doors of the Baptistry, Florence (1425)

Interior of the Church of the Gesù, Rome

Borghese Chapel, Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome

Salvador Dalí's Perseus

In the modern period, images of subjects are disordered—look at the odd proportions and positions of body parts in Picasso's work. We see abstraction and surrealism. The general picture is of chaos, madness, or even sickness. (I'm reminded of Fellini's film 8 1/2, where the main character, trapped in his car in a tunnel in a traffic jam, is seized by claustrophobia, rolls down the car window, and climbs out.) The art, and the greater seeking for psychological help, seems to reflect the sorrows of the changes and conflicts of the Twentieth Century: the Russian Revolution, two World Wars, the Holocaust, the atomic bombs. The glorification and idealization of man in the Renaissance and the search for knowledge of the Age of Reason have put the tools of destruction into the hands of the man of Europe, and with them, he has nearly blown himself up. He has not yet, however, reached his end, and that gives cause for hope. If Europe is less religious than America, Europe, having been more directly torn apart by this turmoil, is in a much more skeptical and reflective position than America. Europe is still very much recovering from the two World Wars—spiritually and psychologically. We could view this period as a culture-wide or continent-wide examination of conscience. When Europe emerges, there will be something very different in its values and in its ideals and practices.

I believe it will take a very large, culture-wide effort of planning and soul-searching to set the top aright and set it moving stably once again. It will require a complete revaluation of our history, of our languages, of our culture, and of our beliefs—in other words the tremendous pangs of labor—before we can give birth to a new culture with new values (and probably a new religion). As it stands, our traditional values are not in place—new developments in science and in politics have put us radically out of touch with the Christianity of the Middle Ages. One has only to compare the art of Giotto with the art of Picasso to see this. And a return to such values is simply not possible, given the journey that we have made and the knowledge that we have incorporated along the way.

Interestingly enough, a sharp decline in Europe's religiosity can be noted around the time of the Age of Reason. This was the era that produced Thomas Jefferson, Isaac Newton, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. This period represented an emphasis on logic in philosophy, objectivity and fair representation in governance, the dominance of form and aesthetic beauty in the arts and architecture, and scientific investigation into the phenomena of the natural world.

What we see, then, as early as two centuries ago is a breakdown in the traditional values and norms of Europe. This paves the way for the Koyaanisqatsi, the Götterdämmerung, of today—for a civilization out of touch with itself, out of sorts, and spinning ever more wildly like a top losing momentum, ready to fall over and stop turning altogether.

Last week I began reading Sigmund Freud's book Civilization and Its Discontents. An interesting idea, which this book presents, is the idea that culture is a spontaneous byproduct of human creativity. When we write a play that plumbs the depths of the human character, such as Hamlet or Oedipus, that is culture. When we build a cathedral with towering pillars, elaborately carved gateways, gilded ceilings, and beautiful stained glass windows, that is culture. When humans act and create, the result is culture. Art and culture, then, are a reflection of ourselves, the creators. If we look at the art of different periods of a culture, we can learn something about the psyche and values of the people who produced that culture. I would like to explore this idea a little further and examine visually some of the cultural landmarks and developments of our European heritage over the last five to seven centuries. (For those of you who are curious: no, beyond a few short paragraphs, I have not yet read Oswald Spengler's Decline of the West.)

The Early and High Renaissance (1300's-1500's)

Form- The word "form" derives from the Latin word forma, which has two meanings: 1) form and 2) beauty. As an example of this, the Latin word formosa survives today as the Spanish word hermosa, and both words have the same meaning: "beautiful." To the Romans, then, form and beauty were synonymous, and it is this connection between the two of them that drives the rebirth of Classical (Greek and Roman) aesthetic values that is known as the Renaissance. During the high period of the Renaissance, form and idealism were the mandates of art and architecture. Aesthetic beauty and visually pleasing figures were sought and, in fact, created in the arts. In the works of Michelangelo and Raphael, we see the epitome of what man can be: a noble creature full of knowledge and wisdom, aspiring towards greater deeds than have ever been accomplished before. Characteristics of this period are aspiration, political ambition, and a spirit of exploration (two continents previously unknown to Europeans are discovered). The body is beautiful and muscular. Proportion and symmetry reign, be it in architecture or the human body. Objects and persons depicted or sculpted resemble the actual objects and persons: there is idealization, but no abstraction. There is reverence for the sacred. Every inch of a painting, of a sculpture, of a cathedral reveals an artist or a priest or a politician glorying in the talent of man. Diagnosis: in the Europe of this time, man is strong, virile, robust, and healthy.Early Renaissance:

Cathedral of Santa Maria di Fiore (Duomo), Florence

Giotto's Mourning of Christ, Scrovegni Chapel (c. 1305)

Giotto's Mourning of Christ, Scrovegni Chapel (c. 1305)

High Renaissance:

Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa (c. 1503–1519) and Vitruvian Man (c. 1497)

Lorenzo Ghiberti's Story of Joseph, Doors of the Baptistry, Florence (1425)

Raphael's School of Athens, from Raphael's Stanze, Vatican Museums (c. 1510)

Click here for a larger image.

Click here for a larger image.

Michelangelo's Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel (c. 1511)

Michelangelo's Last Judgement, Sistine Chapel (1537-1541)

Click here for a larger image.

Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1545)

The Baroque Period (1600's)

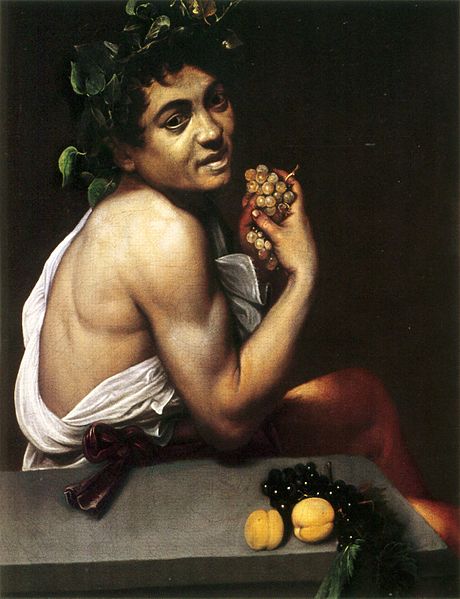

This period is followed by the Baroque period of the 1600's-early 1700's. The Baroque period is typified by extra ornamentation. In architecture, double columns often appear for aesthetic decoration, where only one load-bearer would have sufficed. Enjoyment and mild excess are key to this period; in painting we often see rich gardens and platters of fruits. In painting, chiaroscuro arises: subjects sit in dark backgrounds, lit by a single source of light, which flows over the subjects' contours and casts shadows to the corners. Though highlighting the shadows and lending seriousness to its subjects, the chiaroscuro technique shows a revelry in contemplation.Baroque:

Church of SS. Annunziata, Sulmona

Interior of the Church of the Gesù, Rome

Borghese Chapel, Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome

Chiaroscuro:

Georges de la Tour's Penitent Magdalene (c. 1638-1645)

Caravaggio's St. Francis in Ecstasy (c. 1595)

The Neoclassical Period (late 1700's-early 1800's)

Following the Baroque comes the Neoclassical Period in art. In philosophy, this is also known as the Age of Reason or Age of Illumination, while in music, it is known simply as the Classical period. The word "Classical" means "like the Ancient Greeks and Romans," and the Neoclassical is the second rebirth of Greco-Roman ideals. During this movement, there is a return to the idealization of the human and of the body that was seen in the Renaissance. Majesty, reason, and zeal are characteristic. Greco-Roman myths are often major subjects. Throughout this style, subjects are still clearly recognizable. Lines are clear, edges of subjects and objects are distinct. Beauty is striven for. The tone is heroic.Neo-Classicism:

Jacques Louis David's Death of Socrates

Jacques Louis David's Oath of the Horatii

Jacques Louis David's Napoleon Crossing the Alps

Antonio Canova's Paolina Borghese (Napoleon's sister) as Venus Victrix

Gianlorenzo Bernini's Apollo and Daphne

The Romantic Era and Impressionism (1800's)

On the other hand, when we look at the art of the Romantic era (early to mid-1800's), we see the beginning of a breakdown in forms. Emphasis is now no longer on form and beauty but on feeling and the sublime. Mood is prevalent. Storm and stress (Sturm und Drang) rage in music. Haunting, gothic images abound, in painting as well as literature (Poe, Brontë, and Mary Shelley flourish in this period). We see more shadows, perhaps even mist. Later, with Impressionism, images and sounds become soft and a little blurry. In painting, we see pointillism, points of dots close enough together to seem to be an image, when viewed from a distance. Emphasis is no longer on distinct edges but on more vague impressions of images. With the Romantic period, form has broken down, and with Impressionism, the fragments of form are beginning to melt as if into jelly.Romanticism:

Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer Above the Mists

John Henry Fuseli's The Nightmare

Pointillism and Impressionism:

Georges Seurat's Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884)

Van Gogh's Self-Portrait (1887) Auguste Rodin's Adam (1880)

Claude Monet's Water Lilies (1907)

Claude Monet's Water Lily Pond and Weeping Willow (1916-1919)

The Modern Period (1900's)

What we see in the Twentieth Century, then, is the complete breakdown of form in art. We may still like the artwork or dislike it, love it or hate it. But in visible contrast to the earlier Renaissance and Classical periods, emphasis is no longer on idealization, aesthetic beauty, or form. We see images which would traditionally be viewed as chaotic, abstract to the point of being completely unrecognizable, and sometimes what many would call, in grossly subjective terms, ugly. We can also hear this in the dissonance of the music, Igor Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, for example. It is significant that art begins to look ugly right around the time that psychology and psychoanalysis emerge. Art, as a product of our psyche, is a reflection of us as a culture. We begin to see grossness and chaos in the arts as we begin to see these things in ourselves and go to doctors to seek mental treatment.Expressionism:

Edvard Munch's The Scream

Futurism:

Umberto Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913)

Cubism:

Pablo Picasso's Untitled (1923) Pablo Picasso's Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1910)

Surrealism:

Salvador Dalí's Persistence of Memory (1931)

Salvador Dalí's Perseus

Abstract Expressionism:

Jackson Pollock's Number 8, 1949

Architecture:

Guggenheim Museum, New York

The Absurd:

In modern times, nothing is sacred. Sometimes in these advanced stages of decay, we get really silly.

Marcel Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q.

(The French pronunciation of these letters gives us

the French words: Elle a chaud au cul,

which means, "She has a hot ass.")

The Pillsbury Dough Boy as The Scream

(currently circulating on Facebook)

In the modern period, images of subjects are disordered—look at the odd proportions and positions of body parts in Picasso's work. We see abstraction and surrealism. The general picture is of chaos, madness, or even sickness. (I'm reminded of Fellini's film 8 1/2, where the main character, trapped in his car in a tunnel in a traffic jam, is seized by claustrophobia, rolls down the car window, and climbs out.) The art, and the greater seeking for psychological help, seems to reflect the sorrows of the changes and conflicts of the Twentieth Century: the Russian Revolution, two World Wars, the Holocaust, the atomic bombs. The glorification and idealization of man in the Renaissance and the search for knowledge of the Age of Reason have put the tools of destruction into the hands of the man of Europe, and with them, he has nearly blown himself up. He has not yet, however, reached his end, and that gives cause for hope. If Europe is less religious than America, Europe, having been more directly torn apart by this turmoil, is in a much more skeptical and reflective position than America. Europe is still very much recovering from the two World Wars—spiritually and psychologically. We could view this period as a culture-wide or continent-wide examination of conscience. When Europe emerges, there will be something very different in its values and in its ideals and practices.

I believe it will take a very large, culture-wide effort of planning and soul-searching to set the top aright and set it moving stably once again. It will require a complete revaluation of our history, of our languages, of our culture, and of our beliefs—in other words the tremendous pangs of labor—before we can give birth to a new culture with new values (and probably a new religion). As it stands, our traditional values are not in place—new developments in science and in politics have put us radically out of touch with the Christianity of the Middle Ages. One has only to compare the art of Giotto with the art of Picasso to see this. And a return to such values is simply not possible, given the journey that we have made and the knowledge that we have incorporated along the way.

No comments:

Post a Comment